Heat Recovery Chillers: Recycling Energy in 24/7 Operations

Using the heat generated by freezers and servers to warm the office spaces.

Credit: Gemini (2026)

Introduction: the thermodynamics of waste

In a traditional building, the heating system fights the cold, and the cooling system fights the heat. They rarely interact. However, a laboratory is a unique thermodynamic beast. Even in the dead of winter, a research facility has a massive internal cooling demand generated by rows of ultra-low temperature (ULT) freezers, server racks, and high-intensity imaging equipment.

For the lab architect and engineer, this presents a paradox: the building is burning natural gas to heat the perimeter offices while simultaneously running cooling towers to reject waste heat from the lab core into the atmosphere. This is thermal mismanagement. As discussed in our hub on net-zero lab design, the path to decarbonization requires closing this loop. The technology that bridges this gap is the heat recovery chiller.

What are heat recovery chillers?

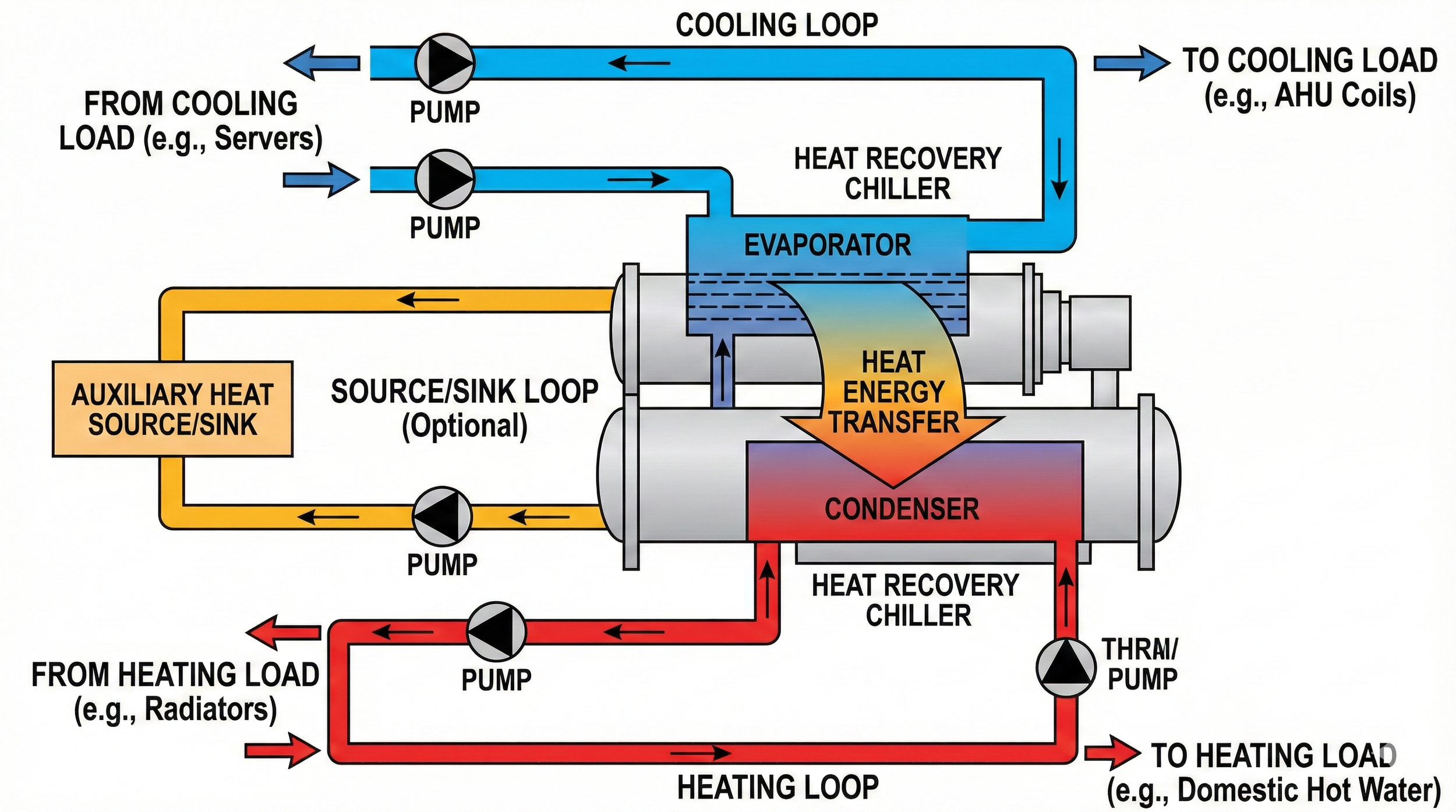

A standard chiller removes heat from a building and rejects it to the outdoors via a cooling tower. Heat recovery chillers are different. They act as "thermal elevators," repurposing energy that would otherwise be wasted.

Heat recovey chillers operate as thermal elevators repurposing energy throught the facility

How it works: The mechanism relies on the standard refrigeration cycle but with a strategic twist.

The Evaporator (Cooling Side): Warm water returns from the lab's cooling loop (carrying heat from freezers and equipment) and enters the chiller's evaporator. The liquid refrigerant absorbs this heat, boiling into a gas and chilling the water typically down to 45°F for recirculation.

The Compressor: This low-pressure gas is compressed, significantly raising its temperature and pressure. This is where electrical energy is input into the system.

The Condenser (Heating Side): Instead of sending this hot gas to an outdoor coil to vent, it passes through a water-cooled condenser connected to the building's heating loop. The hot gas rejects its heat into the water, raising the water temperature (typically from 100°F to 120°F), which is then pumped to reheat coils or domestic water heaters.

This process allows the facility to recycle the energy it has already paid for. The electricity used to cool the -80°C freezers effectively generates the "free" byproduct of hot water, creating a closed energy loop within the facility.

The balance of simultaneous heating and cooling

Heat recovery is most effective in buildings with "simultaneous heating and cooling" loads. Laboratories are the perfect candidate for this profile.

The Cooling Load: Process loads (equipment) and hydronic cooling loops run 24/7, 365 days a year.

The Heating Load: Because labs use 100 percent outside air, the make-up air (MUA) units constantly need heat to condition the incoming supply air. Additionally, VAV reheat coils need hot water to fine-tune room temperatures.

By coupling these systems, a heat recovery chiller can often handle the entire base heating load of the facility during the shoulder seasons (spring and fall) without ever firing a boiler.

Lab HVAC design integration

Integrating this technology requires a fundamental architectural shift in lab HVAC design. In the past, the central plant was designed in silos: boilers lived in one corner, chillers in another, and they never met. Heat recovery requires these systems to speak the same hydraulic language, often physically connecting the condenser water loop (heat rejection) of the chiller to the heating hot water loop of the building. This transforms the central plant from a simple generator of energy into a complex thermal balance manager, moving Btus from the core of the building, where they are not wanted, to the perimeter where they are needed.

Dedicated heat recovery machines

In large central plants, engineers often specify a dedicated heat recovery chiller sized specifically for the facility's "base load"—the minimum amount of cooling required 24/7. For example, a 100-ton heat recovery unit might run constantly to handle freezer farms and server rooms, rejecting its heat into the domestic hot water system. Meanwhile, standard high-efficiency centrifugal chillers remain on standby to handle the peak summer cooling loads that exceed the heat recovery capacity. This ensures the expensive heat recovery unit runs at maximum efficiency year-round.

Connection to energy recovery wheels

While heat recovery chillers recycle heat from hydronic (water) loops, energy recovery wheels recycle heat from the ventilation (air) stream. In a high-performance design, these two systems act as a relay team. The air-side wheels handle the bulk of the heavy lifting—tempering the freezing intake air using the warm exhaust air. The water-side heat recovery chillers then handle the "trim" load, providing the precise temperature control needed at the zone level reheat coils.

The ROI of recycling heat

The financial argument for heat recovery is robust, transforming the central plant from a cost center into an efficiency engine. A dedicated heat recovery chiller typically operates with a combined Coefficient of Performance (COP) of six or higher. In lay terms, for every one unit of electricity consumed, the machine delivers six units of usable thermal energy—three units of cooling to the process loop and three units of heating to the hot water loop.

When compared to a traditional "siloed" approach—running a natural gas boiler (efficiency of 0.8 to 0.9) and a standard air-cooled chiller (COP of 3.0 to 5.0) independently—the combined heat recovery approach can reduce total plant energy consumption by 30 to 40 percent.

The "Spark Spread" Advantage: Historically, the low cost of natural gas made it hard for electric heating to compete. However, because heat recovery chillers operate at such high efficiency, they overcome the "spark spread" (the price difference between electricity and gas). Even if electricity costs four times as much as gas per unit of energy, a heat recovery chiller with a COP of 6.0 delivers heat at a lower operational cost than a gas boiler, effectively decoupling the facility's heating budget from volatile fossil fuel markets.

Conclusion: the circular thermal economy

The days of viewing heat as a waste product are over. In the linear economy of the past, we burned fuel to create heat and used electricity to reject heat. In the circular thermal economy of the modern laboratory, heat is a commodity to be harvested, moved, and reused.

By implementing heat recovery chillers, lab planners can transform the intense energy density of scientific research from a liability into an asset. This approach not only slashes operational carbon but also future-proofs the facility against volatile energy markets and stringent efficiency codes. Ultimately, the most sustainable unit of energy is the one you don't have to buy because you've already generated it. By using the very equipment that consumes energy to help heat the building that houses it, we close the loop on waste.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Do heat recovery chillers work in the summer?

Yes. Even in summer, labs require reheat for humidity control (cooling air to remove moisture, then heating it back up to a comfortable temperature). Heat recovery chillers provide this reheat energy for free, rather than running a boiler in July.

What is the ideal water temperature for heat recovery?

Heat recovery chillers are most efficient when producing Low-Temperature Hot Water (LTHW), typically between 100°F and 130°F. This aligns perfectly with modern condensing boiler loops but may require larger coils in older buildings designed for 180°F water.

Can this replace a boiler entirely?

In most climates, no. A backup boiler is usually required for peak winter loads when the heating demand exceeds the available waste heat from the cooling loop. However, the chiller can displace the majority of the annual natural gas usage.