Hybrid Lab Design: Integrating Wet and Dry Research Zones

The wall between 'Wet' and 'Dry' is disappearing. How to design for the computational biologist.

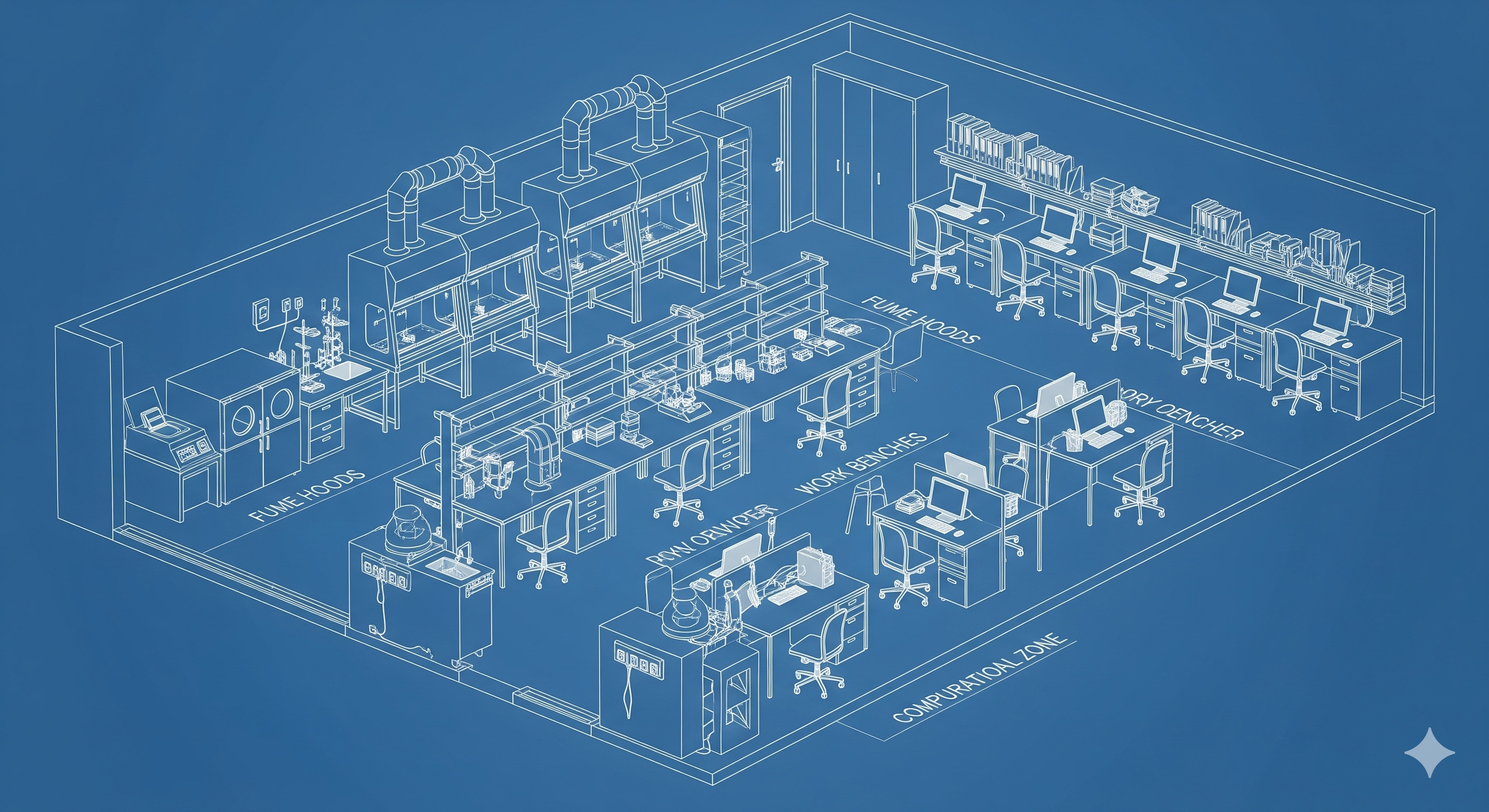

Credit: Gemini (2026)

Introduction: hybrid lab design and the dissolving partition

The era of the "siloed" scientist is over. Traditionally, a researcher spent their day either at the bench (wet) or at a desk (dry), often separated by a hallway, a fire-rated wall, or even different floors. Today, the rise of computational biology, genomics, and bioinformatics has created a new workflow where data generation (pipetting) and data analysis (coding) happen in rapid succession.

For the lab architect and lab planner, this demands a new typology: hybrid lab design. The goal is to lower the "viscosity" of the space—reducing the friction of moving between physical experimentation and digital analysis. Designing a space where a scientist can move from a fume hood to a high-performance workstation without changing PPE or leaving the room is the new frontier of research efficiency.

Hybrid lab design ratios: from 70/30 to 50/50

Historically, the industry standard for life sciences was a 70:30 split—70 percent wet lab to 30 percent dry office. However, as "in silico" experimentation becomes as critical as "in vivo," that ratio is shifting toward 50:50 or even inverting.

The challenge for the laboratory designer is that this ratio is not static. A research group might be heavy on synthesis (wet) in year one and heavy on data modeling (dry) in year two. Hard-walling these zones creates a rigid constraint. Instead, hybrid lab design creates a fluid gradient where the boundary line can move.

Designing the transitional zone

The core of hybrid design is the creation of transitional lab zones—areas that are technically part of the lab environment (allowing for safety oversight and proximity) but are zoned for low-risk, dry activities.

The "write-up" bench

The modern solution is to integrate "write-up" stations directly at the end of wet bench runs. By using a "ghost corridor" or a distinct floor pattern to denote the transition, researchers can step away from a wet experiment to log data on a laptop without passing through a door.

Safety Note: This requires careful HVAC planning to ensure airflow moves from the "clean" dry zone toward the "dirty" wet zone, preventing chemical vapors from drifting into the computational area.

Hybrid lab design infrastructure: handling heat density

Integrating computational biology space into the lab footprint introduces a new mechanical conflict. Wet labs are driven by air change rates (ACH) and exhaust requirements, while dry computational zones are driven by cooling loads.

The HVAC balancing act

Wet Zones: Require 100 percent outside air (single-pass) to exhaust contaminants.

Dry Zones: Typically use recirculated air for energy efficiency.

In a hybrid open plan, the lab planner must often specify a robust system that can handle the high heat output of servers and multi-monitor workstations while maintaining the directional airflow required for safety. This often means over-sizing the cooling capacity in the transitional lab zones to account for the heat density of high-power computing hardware.

Furniture solutions for hybrid lab design

To truly lower the viscosity of the space, the furniture must bridge the gap. Standard office desks look out of place in a lab, and standard steel benches are uncomfortable for coding.

The solution lies in modular laboratory furniture that crosses the divide. Using the same mobile bench chassis for both wet and dry areas creates visual continuity. In the dry zone, the chemical-resistant resin top is replaced with a laminate surface, and the gas valves are replaced with high-density power and data ports.

As detailed in our hub article on flexible lab design, utilizing mobile casework allows the "dry" zone to encroach on the "wet" zone (or vice versa) simply by rolling tables.

Data infrastructure in hybrid lab design

In hybrid lab design, data is as critical as water or electricity. Computational biology space requires more than just Wi-Fi. These zones need hard-wired, high-speed connections (Cat6A or fiber) linked directly to the institution's servers or cloud interface to handle terabytes of genomic sequencing data.

Lab architects must ensure that ceiling service carriers or floor boxes in the transitional zones are saturated with data ports. A common failure in hybrid design is underestimating the cabling requirements for a bioinformatics workstation, which often includes three monitors and a dedicated local processor.

Conclusion: the friction-free workflow

The success of a modern laboratory is measured by the velocity of discovery. Every time a researcher has to de-gown, wash hands, and walk down a hall to check a simulation, friction is introduced. By embracing hybrid lab design and integrating wet lab dry lab ratio flexibility, architects create a frictionless environment. In these spaces, the tools of science—whether a pipette or a Python script—are always within arm's reach.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Can you have carpet in a hybrid lab zone?

Generally, no. Even in the "dry" transitional zones within the lab proper, chemical-resistant flooring (like rubber or seamless vinyl) is recommended. This allows the zone to be converted back to wet use if needed and simplifies cleaning protocols.

How do you manage noise in a hybrid lab?

Wet labs are noisy due to fume hoods and freezers. Dry coding requires focus. Lab planners should use high-performance acoustic ceiling tiles and possibly glass partitions that provide sound isolation while maintaining visual connection between the wet and dry zones.

What is the ideal lighting for computational zones?

While wet labs need bright, cool task lighting (50-70 foot-candles), computational zones need lower ambient light to prevent screen glare. Dimmable LED fixtures or task lights at the dry benches allow researchers to adjust the environment for coding.