A Cutting-Edge Hub for Coastal Science at William & Mary

Rendering of the exterior of Chesapeake Bay Hall from street level. Image: Courtesy of Baskervill

On April 10, 2025, William & Mary’s Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) celebrated the grand opening of Chesapeake Bay Hall, a $76 million, 68,240-sf research facility that marks a transformative moment in the institutions’ 85-year legacy. The project was designed by Baskervill along with their lab design partner, Page; built by Kjellstrom and Lee; and engineering services were provided by RMF Engineering.

Unique coastal and marine science lab spaces

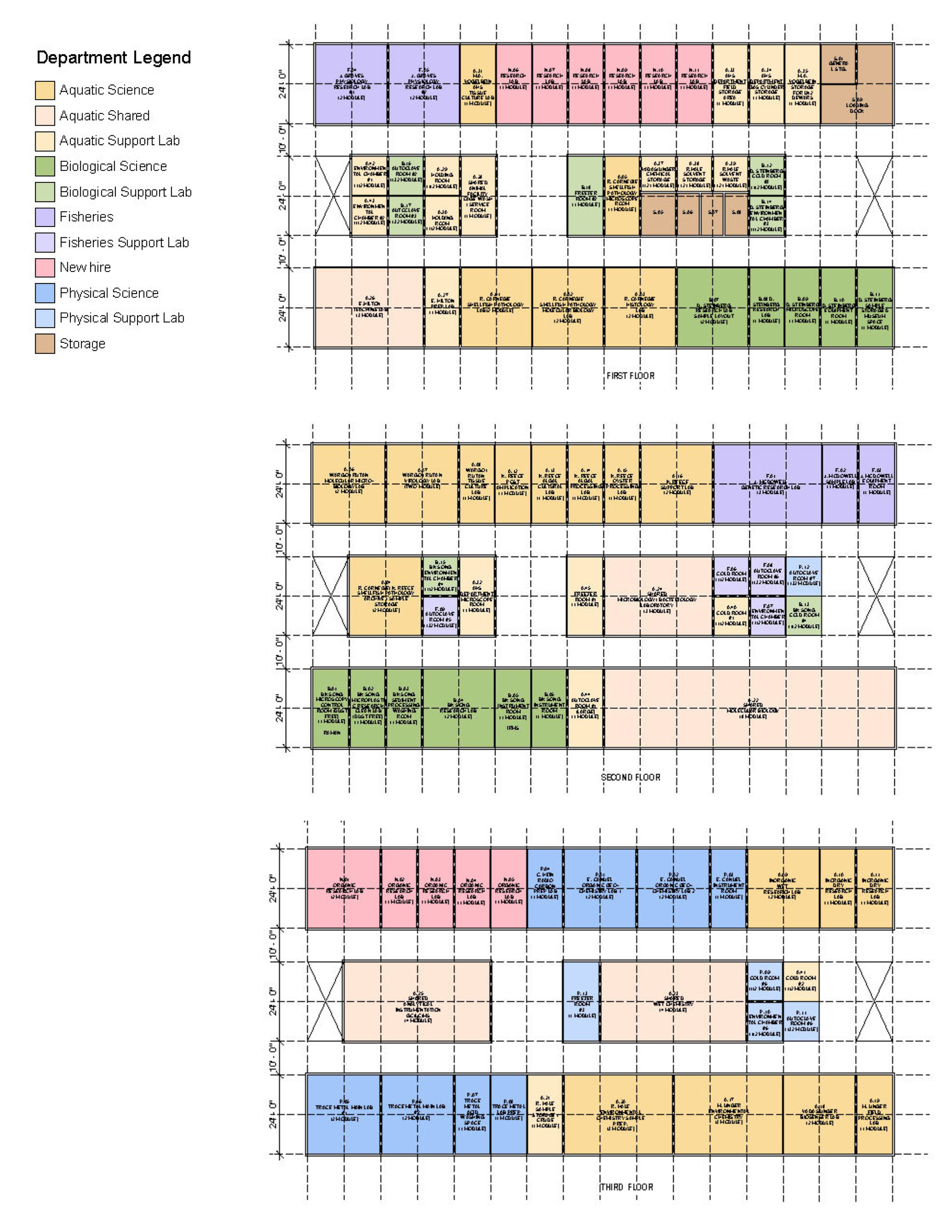

Chesapeake Bay Hall accommodates lab facilities for Aquatic Health Research, Biological Research, Fisheries Research, and Physical Research. These spaces were designed after meeting with researchers and lab users.

“The research labs are designed to provide ample bench space to the users for their everyday operations and special equipment,” says Wisam Aldabbagh, associate principal, lead lab planner with Page. “The program also includes lab support spaces such as controlled environmental rooms, walk-in growth chambers, shared freezer rooms, shared autoclave rooms, shared microscopy, shared DNA/RNA sequencing suite, and spaces for radiocarbon and analytical instrumentation with overhead unistrut framing grid to provide power and service drops to island benches or floor mounted instruments.”

The building features two cleanrooms, one for trace metal research and the other for microplastic research. Both rooms are constructed from non-metal panels and furnished with polypropylene fume hoods, laminar flow clean bench, and casework. Other support spaces are designated for sediment washing, algal culture and processing, and oyster processing.

Rendering of the main entrance of Chesapeake Bay Hall. Image: Courtesy of Baskervill

“It was critical that we base the design of Chesapeake Bay Hall on the lived experience of those who will use the space daily,” says Justin Sculthorpe, AIA, principal, design director with Baskervill. “Through extensive engagement during the planning process, faculty and researchers identified key challenges in the existing 1996-built facility—most notably, deteriorating mechanical systems, a failing façade, and a lack of spatial efficiency that limited collaboration. The previous facility had become a barrier to progress. To address these concerns, the design team worked closely with VIMS to understand their workflows, pain points, and long-term goals. Their input shaped every decision, from the strategic placement of the building on campus to its programming.”

Designing to reflect local history

Designing a high-performance laboratory facility is never a simple task—but doing so on a historically significant coastal site brought an added layer of complexity. For the team behind the project at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), every design choice had to balance modern performance goals with the site's environmental sensitivities and rich cultural history.

Rendering of the north facade with Chesapeake Bay glass visual at dusk. Image: Courtesy of Baskervil

“The design and construction process required careful navigation of buried Revolutionary and Civil War-era archaeological artifacts, which influenced both building placement and site planning,” says Sculthorpe. “The proximity to the York River demanded resilience against moisture and corrosion while showcasing VIMS’ established campus palette—brick, metal, and glass. Compounding those challenges, the project was paused during the COVID-19 pandemic, requiring the team to adapt timelines midstream. In every decision, the design team prioritized longevity, adaptability, and campus cohesion.”

The building’s strategic design was crafted not only for immediate research needs but also with an eye toward future adaptability. The large image of the Chesapeake Bay on the facade reflects the building’s purpose and VIMS’ broader mission, serving as a striking symbol of its connection to the region’s waterways. Visible lab spaces and collaboration zones reinforce the transparency of research, while the mural doubles as a popular selfie spot that helps amplify the institute’s impact.

Sustainability initiatives

In order to meet LEED Silver certification standards, the facility design needed to thoughtfully reconcile ambitious sustainability goals with the heightened energy requirements of a high-performance research facility.

“Energy use was reduced by 22 percent with the design of an efficient HVAC system and selection of Energy Star equipment—all controlled by a building automation system,” says Thomas Mazich, LEED AP, associate, project designer with Baskervill. “Renewable energy is provided by a rooftop wind turbine and an off-site solar farm. A rainwater management system protects nearby waterways and water use is reduced by 20 percent using low flow fixtures and native drought-tolerant landscaping. Thoughtful material selection, like carpet made from reclaimed fishing nets, and bird-safe fritted glass are visible reminders to occupants and visitors of VIMS’ commitment to the environment. This project also features the first EV charging spaces on campus, located proudly under the feature Chesapeake Bay map design on the north glass.”

A diagram showing the department program plan by floor. Image: Courtesy of Baskervil

With laboratories supporting a wide range of functions—from high-sensitivity chemical analysis to aquaculture testing—the HVAC system had to meet diverse environmental demands. The design team approached this by aligning the zoning strategy with the building’s architectural layout, creating distinct systems for lab and administrative areas.

“A strategy of differential airflows delivered to and from spaces by the ductwork distribution systems are utilized to develop pressure differentials between spaces to control transfer of airborne elements between spaces,” says April Ruggles, PE, RMF Engineering, Baltimore Buildings Division. “The overall building is positively pressurized to the outdoors, limiting unconditioned outdoor air from infiltrating the shell of the building, which would interfere with temperature and humidity control. The laboratory wing is maintained as negatively pressurized with respect to the office wing to prevent the egress of potential contaminants to other parts of the building. Individual laboratories are designed as their own temperature control zones and maintained to a negative pressure differential to the adjacent corridor to provide individual containment. Pressurization sensors monitor the pressure differential across the laboratory doors and alarm when the allowable limits are exceeded.”

Ruggles adds, “The laboratory exhaust fans are equipped with a nozzle designed to entrain outdoor air to dilute contaminants and induce an effective stack height of the exhaust plume above the roof, which allows for heightened safety of the building personnel, as well as nearby homes, businesses, and local environment.”

Promoting engagement

Chesapeake Bay Hall will play a key role in the launch of William & Mary’s new undergraduate major in coastal and marine sciences this fall. Faculty, students, and visiting groups alike will benefit from the facility’s teaching laboratories, which are designed to support immersive, hands-on learning experiences.

Chesapeake Bay Hall under construction. Image: Courtesy of Baskervil

“At VIMS, education, research, and outreach aren’t separate tracks—they’re deeply intertwined. The building supports the rigorous demands of advanced research while also creating intentional moments for engagement—reflecting the dual role of graduate students as both learners and researchers,” says Jay Woodburn, AIA, LEED AP, principal, architect with Baskervill. “At the same time, the design clearly defines public and private zones. Windows into lab spaces offer ‘science on display,’ giving visitors a view into the work without physically entering the labs. This strategy optimizes engagement opportunities without disrupting the integrity of the research. When I walk the building now, I’m pleased to see that those lab doors are open much of the time, so their vibrant community stays even more connected and welcoming.”

To encourage interdisciplinary collaboration while maintaining safety and efficiency, the design team implemented a range of strategies—focusing on visibility, shared lab spaces, and informal gathering zones that bring teams together across disciplines.

“The layout of the original facility kept teams isolated, making collaboration a challenge. The new facility was intentionally designed to break down those barriers. Researchers must now leave their labs to access shared amenities like offices and break areas, naturally encouraging spontaneous conversations,” says Matthew Marsili, CID, NCIDQ, principal, director of design with Baskervill. “This shift is supported by three collaboration zones on every floor. The second and third floors feature collaboration spaces directly behind the iconic Chesapeake Bay fritted glass—creating a striking visual connection that literally showcases the building’s mission of openness and innovation from the inside out.”

West facade rendering. Image: Courtesy of Baskervil

Chesapeake Bay Hall’s lab research wing was designed around a modular laboratory concept, allowing the space to be easily adapted as research needs, equipment, and technologies evolve. By grouping flexible lab modules with support areas, offices, and collaboration spaces into cohesive “lab neighborhoods,” the facility can accommodate a wide range of future scientific programs and workflows.

“The goal of organizing these spaces was to maximize the opportunities for creative collaboration yet balance the needs of specific equipment and movement of materials,” says Aldabbagh. “During the design phase of the project, the team reviewed and verified the program to find and cut redundancy, which translated to deleting lab spaces that are no longer supported by any research program. The design is focused on supporting the visions and goals of VIMS while accommodating minor revisions to lab spaces to make sure they work for the scientists and lab users.”

User satisfaction and impact

As a hub for interdisciplinary collaboration, sustainable innovation, and advanced research, Chesapeake Bay Hall represents more than just a facility—it’s a lasting investment in the future of coastal and marine science. The design team notes that positive feedback from end users has affirmed the building’s success.

“One of the most exciting moments during construction was when the glass arrived and the facade started to take shape. It was a standout moment for the team, especially when people started snapping photos of the iconic Chesapeake Bay map visual on the north facade; it was clear the building was already making an impact, even before it was fully finished,” says Jay Woodburn, AIA, LEED AP, principal, architect with Baskervill. “At the dedication, a primary lab user mentioned how invaluable the new facility has been for fostering collaboration that may not have happened before. That personal feedback really hit home, confirming that we successfully created the dynamic, interconnected environment we aimed for.”